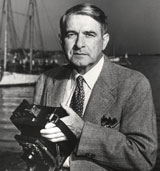

Morris “Rosy” Rosenfeld

Budapest, Hungary; U.S. Citizen: July 28, 1904 Brooklyn, New York

February 16, 1885

– September 21, 1968

Morris “Rosy” Rosenfeld

Budapest, Hungary; U.S. Citizen: July 28, 1904 Brooklyn, New York

February 16, 1885

– September 21, 1968

The Dean

As his late son Stanley writes in the introduction to A Century Under Sail, Morris Rosenfeld shared his first camera with four other boys when he was a teenager in lower Manhattan. He won five dollars in a photo contest, bought his own camera, and went on to take our collective breaths away with the stunning marine images he created. Rosenfeld’s assignment work out of his Nassau Street studio in New York in the early 1900s brings that era poignantly alive, but it is his striking photographs of the great yachts of the day under sail – their clouds of canvas stretched against the sky, their bows plunging through seas as they battle the elements and one another on race courses – that we treasure. Like the best art, many of Rosenfeld’s photographs command our rapt admiration even when viewed over and over again, year after year. In The Sandbagger, 1893, the thin dark quarter wave and the neat, white mustache at the bow on flat water of pounded silver attest to the undisturbed speed of the boat with subtle eloquence. For a vision of pure power, it’s hard to beat the tension in the shot of two 100-foot tops’l schooners, Ingomar and Elimina, 1907, racing hard on the wind with acres of sail dark in the backlight and seas aglitter with gusts over 20. The huge M sloops, Prestige and Windward, beating to weather on Long Island in 1930 with their rails foaming from stem to stern and sails dark against gray skies, is another. The schooners Water Gypsy and Nina knocked down in Dry Squall is a critical moment of yachts and crews being tested. [The complete Rosenfeld Collection is at the Mystic Seaport Museum.]

Today’s small, smart cameras are computers with lenses and digital chips that hold hundreds of images, making photography everyman’s pursuit. But good marine photographers are still scarce. Consider Morris Rosenfeld tackling the elements from a bouncing chase boat with a heavy box camera (on a tripod) that required glass plates, focusing on an upside-down image moving backwards. Black and white photography is an abstract medium. The artistic magic Rosenfeld worked in the darkroom accounted for much of the impact of the resulting silver gelatin prints, in which the mass of every element is emphasized. A crafty man, Rosenfeld had a file of handsome sky photographs he superimposed behind images of boats for those times when the weather hadn’t cooperated.

Morris Rosenfeld was said to be a diligent man, aggressive, with a commanding presence. “[He] had a deep-rooted appreciation of the sea, an innate artistic eye, and a comprehensive knowledge of photography,” Stanley writes. “He was very good at catching the significant moment and, just as important, good at being there when it happened.”

~ Roger Vaughan